|

Why is understanding the different probiotic strains so important? Understanding the importance of different probiotic strains The importance of the gut microbiome Scientific research has helped to reveal an additional organ system that has been invisible to the naked eye for much of human history: the gut microbiome. Just like we need lungs to breathe and a heart to pump blood around our bodies, we now know that the community of microorganisms living in our gut operates like a vital organ and is just as crucial for our health (1). When the gut microbiome is healthy the whole body benefits. However, just like any other organ, the gut microbiome can become disrupted and negatively impact our health. This is referred to as ‘gut dysbiosis’ and it has now been associated with many chronic diseases, including irritable bowel syndrome, depression, asthma, acne, osteoporosis and countless others (1). The rise in gut dysbiosis (and its negative health effects!) are thought to be due to several factors. Changing diets with lower intakes of fibre and unrefined plant foods, stressful lifestyles, low activity levels and increased use of antibiotics – these factors reduce the population and change the types of microorganisms found in the gut, creating gut dysbiosis.

Fortunately, probiotics have emerged as a way to intervene. What is a probiotic and how do they work? Probiotics are living microorganisms that have been found to be beneficial to health when taken as a supplement. Within the gut, probiotics that we take and the microorganisms that live in our body perform many different biological actions that can influence our health. They

use the food we eat to grow and replicate, and, through this process, they

produce compounds called metabolites which we absorb like nutrients. These

metabolites can travel through circulation and interact with other body

systems. They can also interact with the different types of cells in our gut,

including:

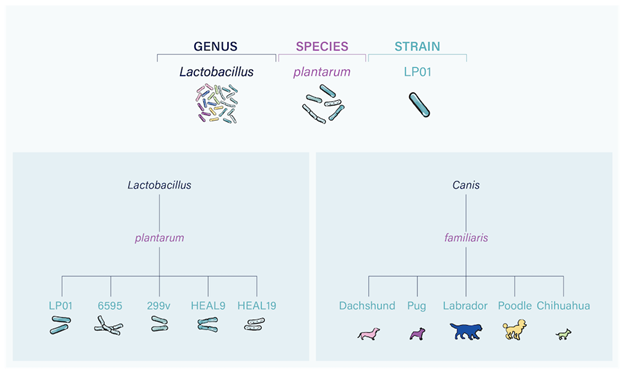

These interactions can change how the cells function and the messages they are sending to other parts of the body. This interaction with the rest of the body means that the microorganisms and probiotic bacteria in the gut can impact other organ systems and, as a result, many aspects of human health. Different probiotic supplements will offer different health benefits, and this all depends on the probiotic strains being used (2). What is a probiotic strain? As in the plant kingdom, probiotic bacteria are classified according to the family, genus and species they belong to. Bacteria from the Bifidobacterium genus are commonly found in probiotic supplements. There are over 24 different species of Bifidobacterium that can be used, such as Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium longum and Bifidobacterium infantis. Despite being similar, they all have noticeable differences. Interestingly, bacteria within the same species can still be quite different. For that reason, they are further classified into individual strains such as Bifidobacterium breve BR03 or Bifidobacterium breve B632 (with the BR03 and B632 being the strain names). Even

if two probiotics are of the same species, the genetic variation between

different strains can be as significant as the difference between a human and a

lemur (3). Because of these differences, each strain of probiotic bacteria will

perform unique biological actions in the gut and therefore offer different

health benefits. Just like medications, not all probiotics work in the same

way.

What are some strain-specific health

benefits of probiotics?

Knowing

this information helps us to select probiotic strains that will address our

specific set of health concerns and improve our health in a targeted way. When

a probiotic supplement doesn’t identify the specific strains being used, it is

very difficult to know how they will benefit your health (if at all).

Generalised statements about the benefits of a species, such as “acidophilus is

good for people with IBS” or “plantarum is good for your mood", are often

incorrect. Quality research investigating the benefits of a probiotic will

always be attached to a specific strain or a group of strains that have been

researched together, not the species.

What areas of health can be targeted with specific probiotic strains? While there are many strains that possess the ability to support our digestive health in some way, there are also specific strains which can target aspects of human health well beyond the gut. Eczema For example, Ligilactobacillus salivarius LS01 is a probiotic strain which has been shown to help regulate the immune response that contributes to eczema in the skin (4). In a human clinical trial, LS01 helped to significantly reduce the symptoms of mild eczema after 4 months of treatment when compared to placebo (5). The participants who took LS01 had a 52% reduction in the severity of their symptoms Dental plaque and gum inflammation There is a specific combination of probiotic strains that, across several human clinical trials, has been found to help significantly improve gum health and reduce dental plaque accumulation: Lactobacillus helveticus Rosell®-52, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus Rosell®-11, Bifidobacterium longum Rosell®-175 and Saccharomyces boulardii (CNCM I-1079). In one randomised placebo-controlled trial, use of this probiotic combination as a mouthwash over 14 days reduced plaque accumulation by 71% and gum inflammation by 73% compared to placebo (p<0.05). These results were as good as the conventional mouthwash chlorhexidine (6). Immunity Specific probiotic strains demonstrate significant

immunostimulatory effects by interacting with the immune tissue lining the gut.

The circulation of immune cells ensures that beneficial effects of these

probiotic strains can be transferred to all mucosal tissue (including the

respiratory tract) for improved immunity throughout the body. Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG is one

of the most well-researched probiotic strains for children’s immune health.

Meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials found that L. rhamnosus GG reduces the incidence of

upper respiratory tract infections by 38% and use of antibiotics by 20% in

children (7). In adults, the combination of Lactiplantibacillus

plantarum HEAL9 and Lacticaseibacillus

paracasei 8700:2 has been found to significantly reduce the incidence of common

colds by 29% and reduce their severity by 38% when compared to placebo (8, 9).

There

are many more health concerns which can be improved through the use of specific

probiotic strains, including IBS, vaginal health, iron absorption and more.

With scientific research only scratching the surface of how the gut microbiome

affects human health, it is expected that the application of specific probiotic

strains for the management of specific health concerns will continue to expand.

Selecting appropriate therapeutic doses and durations of treatment Therapeutic doses and durations of treatment for probiotics are determined by clinical research and may differ for each probiotic strain and the health concern being targeted. The prescribed dose and duration should be informed by the dosing regimens that were found to be therapeutic within the clinical research. For example, a combination of Bifidobacterium breve BR03 and Bifidobacterium breve B632 was found to help reduce the average daily crying time in bottle-fed infants administered 100 million CFU of each strain daily for three months (10), while an 8-week treatment with 1 billion CFU of each strain had beneficial effects on insulin sensitivity in paediatric obesity (11). It is important to prescribe the same daily dose for the same amount of time as in the supporting clinical trials to increase the likelihood of achieving similar results, and the probiotic supplement selected should include a dose that reaches or goes beyond its therapeutic threshold. Ensuring probiotic viability Probiotics are living microorganisms that can be destroyed by adverse environmental conditions during storage, including exposure to moisture before administration. This can occur if a probiotic product is not packaged or stored appropriately. Packaging methods that help to mitigate this risk include the use of opaque blister packs and single-serve sachets. These methods provide individual microenvironments to each serve, shielding probiotic bacteria from the damaging effects of environmental moisture as well as oxygen and UV light and providing each serve with the same protection as an unopened jar. Probiotic supplements contain dormant living bacteria which become metabolically active and start delivering their health effects when they reach the optimal conditions of the human colon. In order for this to occur, probiotic bacteria must survive transit through the destructive low pH of stomach acid. Some studies suggest up to 80% of probiotic bacteria are killed following transit through the upper gastrointestinal tract (12). Therefore, probiotic bacteria often need extra protection in order to reach the colon alive. This can be achieved through specialised delivery technologies, such as clinically validated microencapsulation. Achieving effective probiotic prescriptions By understanding these variables which influence the effectiveness of a probiotic prescription, clinicians can analyse the many different probiotic supplements available to them and ultimately make the most appropriate selection for their clients. By matching health goals to specific probiotic strains, reviewing clinical evidence, understanding the required dose and duration of treatment, and considering features which influence probiotic viability, clinicians can achieve effective and evidence-based probiotic prescriptions. Activated Probiotics Each of our products has been carefully formulated with specific probiotic strains that target a particular health concern, creating a range of condition-specific probiotics products Our range includes complete product formulations and specific probiotic strains which are backed by a high level of clinical evidence. Results from randomised double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trials support the targeted health benefits of each of our Activated Probiotics products.Sources

|